Good continuation would suggest that we are more likely to perceive this as two overlapping lines, rather than four lines meeting in the center.

Gestalt law of similarity series#

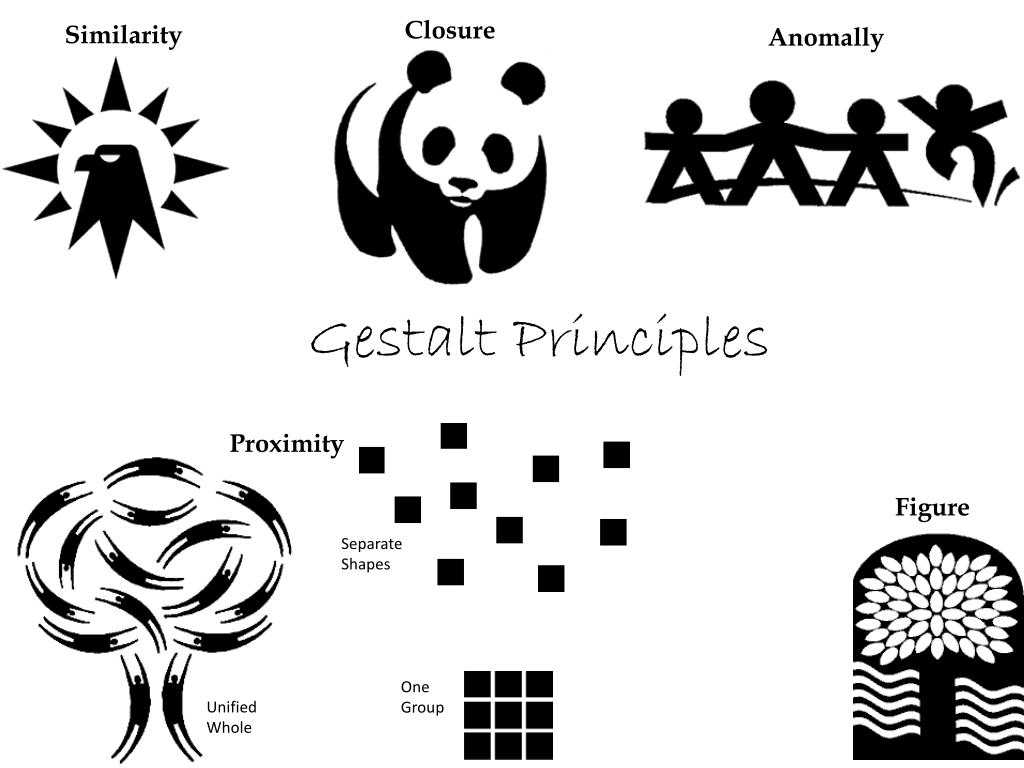

The principle of closure states that we organize our perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts ( Figure).

The law of continuity suggests that we are more likely to perceive continuous, smooth flowing lines rather than jagged, broken lines ( Figure). Two additional Gestalt principles are the law of continuity (or good continuation) and closure. We are grouping these dots according to the principle of similarity. When looking at this array of dots, we likely perceive alternating rows of colors. When watching an offensive drive, we can get a sense of the two teams simply by grouping along this dimension. For example, when watching a football game, we tend to group individuals based on the colors of their uniforms. According to this principle, things that are alike tend to be grouped together ( Figure). We might also use the principle of similarity to group things in our visual fields. Here are some more examples: Cany oum akes enseo ft hiss entence? What doth es e wor dsmea n? We group the letters of a given word together because there are no spaces between the letters, and we perceive words because there are spaces between each word. For example, we read this sentence like this, notl iket hiso rt hat. How we read something provides another illustration of the proximity concept. The Gestalt principle of proximity suggests that you see (a) one block of dots on the left side and (b) three columns on the right side. This principle asserts that things that are close to one another tend to be grouped together, as Figure illustrates. The concept of figure-ground relationship explains why this image can be perceived either as a vase or as a pair of faces.Īnother Gestalt principle for organizing sensory stimuli into meaningful perception is proximity. Presumably, our ability to interpret sensory information depends on what we label as figure and what we label as ground in any particular case, although this assumption has been called into question (Peterson & Gibson, 1994 Vecera & O’Reilly, 1998). As Figure shows, our perception can vary tremendously, depending on what is perceived as figure and what is perceived as ground. Figure is the object or person that is the focus of the visual field, while the ground is the background. According to this principle, we tend to segment our visual world into figure and ground. One Gestalt principle is the figure-ground relationship. As a result, Gestalt psychology has been extremely influential in the area of sensation and perception (Rock & Palmer, 1990). Gestalt psychologists translated these predictable ways into principles by which we organize sensory information. In other words, the brain creates a perception that is more than simply the sum of available sensory inputs, and it does so in predictable ways. The word gestalt literally means form or pattern, but its use reflects the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. This belief led to a new movement within the field of psychology known as Gestalt psychology. Wertheimer, and his assistants Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka, who later became his partners, believed that perception involved more than simply combining sensory stimuli. In the early part of the 20th century, Max Wertheimer published a paper demonstrating that individuals perceived motion in rapidly flickering static images-an insight that came to him as he used a child’s toy tachistoscope.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)